“The Ideal Book”: William Morris and the Kelmscott Press

“I BEGAN PRINTING BOOKS WITH THE HOPE OF PRODUCING SOME WHICH WOULD HAVE A DEFINITE CLAIM TO BEAUTY, WHILE AT THE SAME TIME THEY SHOULD BE EASY TO READ AND SHOULD NOT DAZZLE THE EYE” – WILLIAM MORRIS, 1895

In 2021 The William Morris Society celebrated 130 years since the founding of William Morris’s Kelmscott Press and 125 years since the Press’s publication of the Kelmscott Chaucer, its crowning work and one that embodied Morris’s highest design ideals.

William Morris had a lifelong interest in the art of book printing and design. Following the Industrial Revolution, book production, as with many manufactured goods, became subject to increased mechanisation.

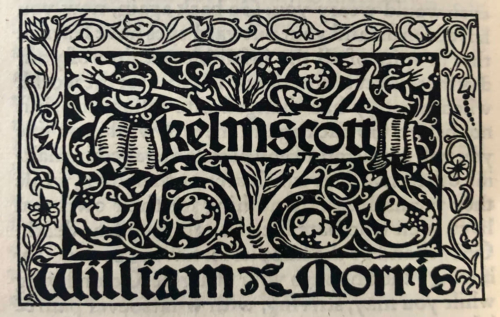

Colophon From News From Nowhere, 1893

Morris perceived this automation as constraining the worker’s creativity and resulting in a reduction of quality. Rather than looking back to the standards of book printing just before the Industrial Revolution, Morris felt the pinnacle of printing was at its outset, when German innovator Johannes Gutenberg revolutionised book production with the introduction of movable type in the fifteenth century.

In the 1860s Morris made minor forays into book design but did not devote his fuller efforts and concentration to it until the late 1880s. In 1888, Morris attended a lecture at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society delivered by his neighbour and friend, Emery Walker, an accomplished photographer and engraver. The lecture was about typeface design and featured a series of lantern slides that showed type from early printed books.

This lecture was a defining moment, inspiring Morris to design the Kelmscott Press typefaces, a key element that had been absent from his early attempts at book design. Walker declined an invitation to be an official partner in the Press, but his expertise and guidance were critical to its success.

Albion Printing Press, Manufactured by Jonathan and Jeremiah Barrett

Circa 1835

Iron

The Kelmscott Press owned three Albion iron hand presses and one smaller press during its seven years of operation.

The William Morris Society is fortunate to have within its collection one of the Press’s full-sized Albion hand presses, pictured here.

Following Morris’s death (1896) and the closure of the Kelmscott Press (1898) the Society’s Albion was purchased and used by a variety of individuals and organisations. These included; C.R. Ashbee, who used the press for his Essex House Press, Ananda Coomaraswamy, who printed ‘Medieval Sinhalese Art’ on the press and A.H. Bullen who used the press for the Shakespeare Head Press in Stratford upon Avon.

In the 1920s, the Society’s Albion came into the possession of Sir Basil Blackwell and was moved to Oxford, where it was used by the School of Technology until the 1940s. From 1967–1978, Blackwell served as president of the William Morris Society, during his tenure he kindly donated the Albion to the Society, where it resides today. The Albion is still in working order and is used by our trained guides and members of staff to give demonstrations to visitors.

The other two full-sized Albion presses that were used by the Kelmscott Press are in the United States, one is owned by the Huntington Library in California and the other by the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York State. The whereabouts of the fourth smaller press is unknown.

Morris immersed himself in every aspect of book production and gave careful consideration to the materials used. Kelmscott Press books were printed exclusively on Albion hand printing presses, rather than modern cylinder presses. This was because Morris initially assumed the Press would be a small operation, only of interest to himself and a small set of friends and colleagues. A hand press was the clear financial choice for such limited print runs. Despite public interest and demand outpacing Morris’s early goals, the Kelmscott Press did not abandon hand printing presses, which were better suited than cylinder presses to printing ornate detail and printing on handmade paper. The Kelmscott Press began with one Albion Press and would over the course of its operations come to own three presses, to match public demand and accommodate the slower process of printing by hand.

In selecting ink for the Kelmscott Press, it was important to Morris that the ink be manufactured without the chemicals favoured during the period, as he felt older ink formulas would produce results most similar to the Medieval books he admired and hoped to emulate. Nineteenth century ink was thinner, to accommodate the slightly different requirements of modern printing presses. Morris felt these thin inks were substandard and had a ‘grey’ quality to them on paper. Hand printing presses allowed for a thicker ink to be used, a viscosity that gave the inked pages a longer lifespan. Morris experimented with a range of black inks, and settled on the German based company, Gebrüder Jänecke, that had been recommended by Emery Walker.

Red and blue inks also featured in the Kelmscott Press books, being used for smaller embellishments and titles. Blue ink for the Press was sourced and made to Morris’s own specifications, from Winsor and Newton, a London based fine arts company. However, red ink proved challenging, as Morris trialed a variety of red inks but was never fully satisfied with the result, his argument being that none struck the right balance between pink and orange.

The paper used by the Kelmscott Press, was based on examples of fifteenth century paper in books from Morris’s personal library. To achieve this product, Joseph Batchelor and Son of Little Chart, Kent, were contracted to produce hand-made, non-bleached paper in a number of sizes for the Press. Morris personally preferred books printed on paper but recognized the desire for other mediums, and so issued a small number of each publication printed on vellum.

The Kelmscott Press books were bound by the respected London firm, J and J Leighton in two styles; a limp vellum and a simple linen and board. Both bindings were unique choices, as the fashion of the time was leather bound books. This attention to detail and high standard reflect Morris’s artistic process and clear vision for the Kelmscott Press books. The individual supplies and designs employed in the production of the Kelmscott publications became popular and resulted in a number of publishers attempting to imitate the style of Morris’s books.

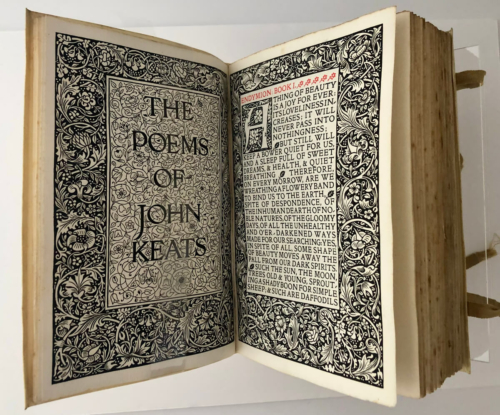

The Poems of John Keats, edited by FS Ellis

Published by the Kelmscott Press in May 1894

Vellum binding with silk ties, paper pages

This Kelmscott Press book is bound in limp vellum, with simple silk ties on either side. The book is one of three hundred copies that were printed on paper, each priced at thirty shillings. The choice to use vellum ran contrary to the popular book styles of the time, but aligned with Morris’s desire to echo the great books of the medieval period.

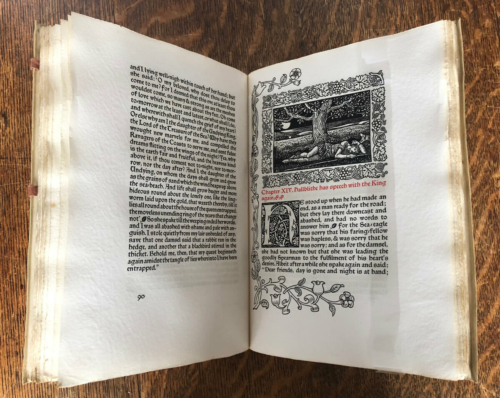

Of the Friendship of Amis and Amile, translated by William Morris

Published by the Kelmscott Press in April 1894

Board and linen binding, paper pages

This Kelmscott Press book is bound in simple boards, covered in handmade paper with a linen spine. This type of binding is known as quarter holland binding. Morris viewed board bindings as temporary coverings, imagining that the book owner would commission a bookbinder to fashion a bespoke binding. However, this was not always the case, as evidenced in this particular copy, which retains the original board binding.

The book is one of five hundred copies that were printed on paper, each priced at seven shillings.

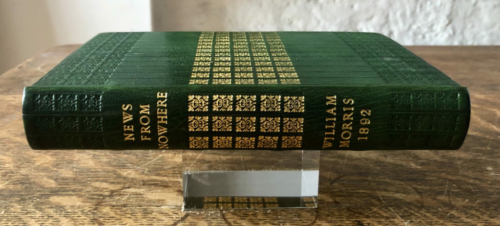

News from Nowhere, written by William Morris Published by Reeves and Turner in March 1893 Leather binding, paper pages

This Kelmscott Press book is bound in a bespoke leather binding with gold embellishments. It was not unusual for book owners to have bindings commissioned, especially for special editions or more rare works. The book is one of three hundred copies that were printed on paper, priced at two guineas each.

The Kelmscott Press began operations in January 1891 in the rented premises of a Georgian cottage, at 16 Upper Mall. The address was especially convenient, as Morris’s London residence, Kelmscott House, was a moment’s walk away.

Five months into their rental of 16 Upper Mall, the Press moved to larger premises next door at 14 Upper Mall, known as Sussex Cottage.

This site would remain the principal home of the Kelmscott Press until its closure in 1898. Maintaining pace with Morris’s ambitions and the success of the Press, they rented an additional cottage space in January 1895, at 21 Upper Mall.

“The designer of the picture-blocks, the designer of the ornamental blocks, the wood-engraver, and the printer, all of them thoughtful, painstaking artists, and all working in harmonious cooperation for the production of a work of art”– william morris, 1892

The Kelmscott Press worked with a few publishers before becoming a publishing body in its own right. Early publishers of Kelmscott books include Reeves and Turner, a London-based company that had a shop along the Strand and leading London bookseller, Bernard Quaritch. Morris took the decision to self-publish because of mounting dissatisfaction with external publishing bodies, particularly their over-involvement in the Press’s operations.

In becoming its own publisher, the Kelmscott Press also advertised its own publications. The Press issued simple lists that detailed upcoming and past works for sale. The comprehensive lists allowed the buyer to plan their purchase, resulting in a number of Kelmscott titles being sold before going to print.

At the beginning of the Press’s operation, a single Pressman, William Bowden, was employed. The work quickly became too much for one printer and the staff was expanded to include Bowden’s son and daughter, WH Bowden and Mrs Pine. WH Bowden later succeeded his father in the role and Mrs Pine became the first woman to join the London Society of Compositors. Throughout the life of the Press, the number of staff increased, keeping pace with its output.

The beautifully detailed illustrations that the Kelmscott Press books are known for were drawn by a number of artists, including Edward Burne-Jones, Walter Crane, Charles Gere and Arthur Gaskin. When illustrations were finalised, they were photographically transferred onto woodblocks and then engraved by hand. Over the course of the Press’s operation, different engravers were contracted. William Harcourt Hooper stands out as a regular engraver for the Press.

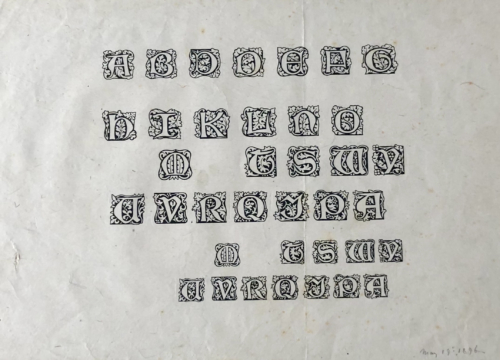

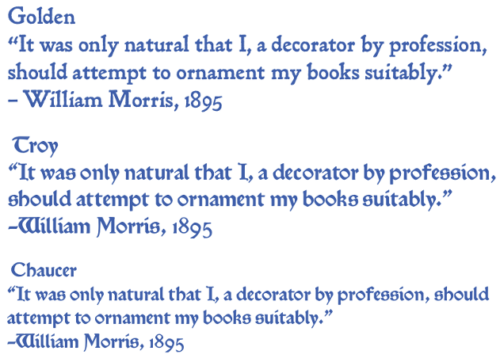

William Morris designed the borders, title pages, initials and three typefaces featured throughout the Kelmscott Press books. To see how the different visual elements worked together on the page, Morris often sketched directly on printed test pages. To design the typefaces for the Press, Morris employed Emery Walker’s company to take largescale photographs of fonts in Medieval books. Morris used the images to closely examine the letters and took inspiration from them to draw his own designs in large scale. The sketches were then photographically reduced, again by Walker, to show the sketched type to book scale. Once each typeface was finalized they were hand cut by a punch cutter. The Kelmscott Press contracted Edward Prince to cut all the typefaces throughout its operation. Prince was well-respected in his industry and was at the time of his death, in 1923, the last living independent punch cutter in England.

The use of photography in the Kelmscott Press is innovative but also significant as Morris is known for his criticism of the industrial age. Morris was not against all technological advancements but rather disputed poor quality products and the inferior workplaces and living conditions brought on by the Industrial Revolution.

Original Design For Initials, Drawn By William Morris, Circa 1891, Ink On Paper

‘Golden’ was the first typeface of the Press and was designed by Morris in 1890. It is a Roman type that was based on a fifteenth century font by Venetian printer, Nicholas Jenson.

A year later, Morris created a Gothic typeface called ‘Troy’. The typeface was named after The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye by William Caxton, which fittingly was the first book the Press printed using the font.

Troy type was inspired by the fifteenth century German printers Peter Schoeffer of Maiz, Gunther Zainer of Augsburg and Anthony Koburger of Nuremberg. Morris designed Troy type with the intention of using it in his planned Kelmscott version of the Canterbury Tales. However, after trial pages were printed the typeface was judged too large for printing Chaucer’s lengthy work. Through the examination of photographic reductions of the type, Morris decided to have it recut to a smaller, 12 point size. The new, smaller version of the typeface was finished in 1892 and aptly named ‘Chaucer’.

The Kelmscott Press published 53 books during its seven-year operation, between 1891 and 1898. The titles printed by the Press reflect Morris’s tastes as well as provide insight into the advisement Morris received from his close friends on works to print. The Press printed a number of Morris’s own works, such as News from Nowhere in 1893 and The Wood Beyond the World in 1894. The first publication issued by the Kelmscott Press was Morris’s fantasy novel, The Story of the Glittering Plain in May 1891.

‘The Story Of The Glittering Plain,’ Written By William Morris, Published By The Kelmscott Press In February 1894, Vellum Binding With Silk Ties, Paper Pages

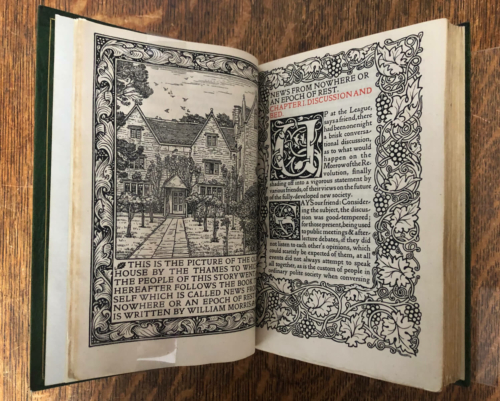

News from Nowhere, written by William Morris

Published by Reeves and Turner in March 1893

Board and linen binding, paper pages

News from Nowhere was first published in 1890 and appeared in serial form in the Socialist League newspaper, The Commonweal. It was then published complete in book form by the Kelmscott Press in 1893. The work is Morris’s utopian vision of a future free from industrialisation and capitalism and is one of a number of socialist novels written by him.

This book is one of three hundred copies that were printed on paper, priced at two guineas each. The Press also issued ten copies printed on vellum that sold for ten guineas each. The book was printed using Morris’s Golden typeface and features both black and red ink throughout.

The Kelmscott Press also published works by contemporary English authors of the period, including The Nature of Gothic by John Ruskin in 1892 and The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1895.

‘The Poems Of John Keats,’ Edited By Fs Ellis, Published By The Kelmscott Press In May 1894, Vellum Binding With Silk Ties, Paper Pages

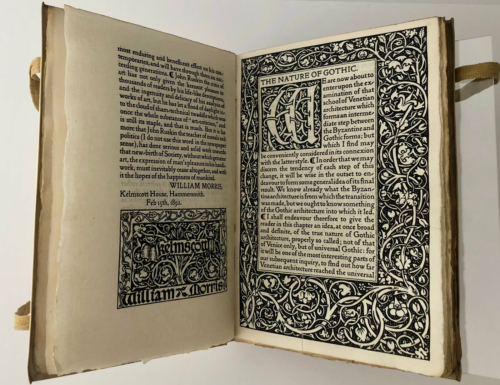

The Nature of Gothic: A Chapter of the Stones of Venice, written by John Ruskin

Published by George Allen in March 1892

Vellum binding with silk ties, paper pages

The Nature of Gothic is a reprinted chapter from John Ruskin’s three volume work The Stones of Venice, that was first released over 1851-3. John Ruskin was a prominent art historian, writer and polymath of the Victorian era and was an inspiration to the Arts and Crafts Movement and William Morris.

The Stones of Venice explores the history of the art and architecture of the Byzantine, Gothic and Renaissance eras. In The Nature of Gothic section Ruskin contends that the Gothic style was embedded in morality and not simply gratuitous decoration. The chapter became significant to the Gothic revival taking place across Europe in the nineteenth century.

Morris first read The Nature of Gothic during his days as a student at Oxford University. The concepts certainly remained with him throughout his life, as Morris stated in his introduction to the Kelmscott edition of The Nature of Gothic, that the work was “one of the very few necessary and inevitable utterances of the century.”

This book the fourth book printed by the Kelmscott Press and is one of five hundred copies printed and sold for thirty shillings each. The book was printed using Morris’s Golden typeface and features both black and red ink throughout.

Morris’s love of the medieval period and its aesthetic led the Press to publish a number of books by medieval authors, such as The Poems of William Shakespeare in 1893 and The History of Reynard the Foxe by William Caxton in 1893. The pinnacle of these Medieval publications, and the Kelmscott Press as a whole, is The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, also simply known as The Kelmscott Chaucer.

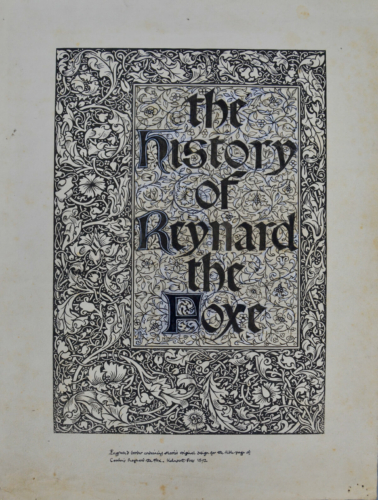

Original design for the title page of The History of Reynard the Fox, drawn by William Morris

Circa 1892

Ink on paper

This piece gives significant insight into the design process for the Kelmscott Press, showing how pages were drawn in full before they were engraved onto woodblocks for printing.

The Kelmscott Press issued William Caxton’s, ‘The History of Reynard the Fox’ in January 1893. The book was a reprint of Caxton’s 1481 translation of an assortment of French medieval animal fables. Caxton brought the technology of the printing press to England, forever changing the landscape of information consumption.

Morris’s decision to reprint Caxton’s work is very fitting, given both men’s shared interest of printing as well as medieval history and literature. The Kelmscott Press printed a total of five William Caxton books.

The Kelmscott Press printed three hundred copies on paper and ten on vellum of ‘The History of Reynard the Fox’. The book was printed using Morris’s Troy typeface and features both black and red ink throughout.

‘The Works Of Geoffrey Chaucer,’ Edited By Fs Ellis, Published By The Kelmscott Press In June 1896, Board And Linen Binding, Paper Pages

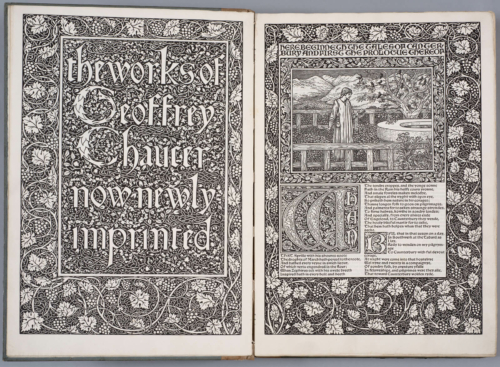

The Kelmscott Chaucer was the last title printed by the Kelmscott Press that was overseen by Morris before his death in 1896. It represents the culmination of Morris’s pursuit of the “Ideal Book” and is widely considered one of the most beautiful books ever printed. It was described by Sir Edward Burne-Jones as “like a pocket cathedral.”

The Kelmscott Chaucer took four years to complete (1892-1896) and was the largest project the Press ever undertook. Morris and Burne-Jones had a shared love of Chaucer’s poetry since their time as students at Oxford and had spoken about printing their own edition of the Canterbury Tales well before the founding of the Kelmscott Press.

All 486 copies of the Kelmscott Chaucer were presold before the book went to print. This popularity led Morris to purchase a third Albion press, that worked almost exclusively on printing the Kelmscott Chaucer. The finished book contains 87 illustrations by Burne-Jones, a woodcut title page, 14 large borders, 18 frames and 26 initial words designed by Morris.

William Morris passed away on October 3rd, 1896, four months after the completion of the Kelmscott Chaucer. Before his death, Morris asked Emery Walker and Sydney Cockerell if they would consider taking over the Press. Walker and Cockerell supervised the printing of the remaining titles Morris had planned before his death but ultimately chose to close the Press to preserve the integrity and quality of Morris’s printing legacy.

The Kelmscott Press finished eleven titles after Morris’s death, including an eight volume edition of Morris’s The Earthly Paradise. Robert Catterson-Smith, who assisted with illustration at the Press, completed Morris’s unfinished ornamental designs. The final book issued by the Kelmscott Press on March 24th 1898 was Morris’s own title – Love is Enough. The Kelmscott Press closed its doors in Spring 1898.

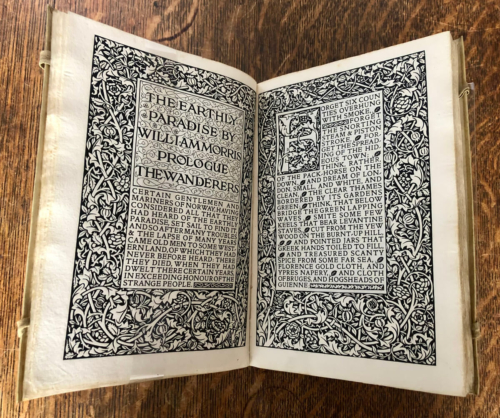

The Earthly Paradise, Volume 1, written by William Morris

Published by the Kelmscott Press July 1896-September 1897

Vellum binding with silk ties, paper pages

The Earthly Paradise was written by Morris over 1868–70. The work is an epic poem in the style of Geoffrey Chaucer. The story follows a group of Norsemen escaping plague, who find their way to an Adriatic island where the inhabitants and refuges share tales from their various homelands.

While writing the work, Morris had initial plans for printing his own edition, complete with designs.

However, his intricate designs did not suit modern typefaces and this, combined with Morris’s other commitments, led to the abandonment of the project until the founding of the Kelmscott Press.

The first three volumes of The Earthly Paradise were printed at the Kelmscott Press in Spring of 1896. Morris passed away in October 1896 and therefore did not see the printing of the remaining five volumes. Morris’s executors printed them, noting in the colophon, “Printed by the Trustees of the late William Morris at the Kelmscott Press.”

This book is one of two hundred and twenty-five copies that were printed on paper, priced at thirty shillings each. The Press also issued six copies printed on vellum that sold for seven guineas each. The book was printed using Morris’s Golden type and features both black and red ink.

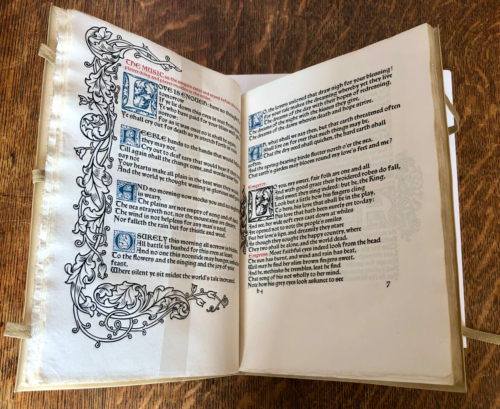

Love is Enough, or the Freeing of Pharamond: A Morality, written by William Morris

Published by The Kelmscott Press in March 1898

Vellum binding with silk ties, paper pages

Love is Enough was written by Morris in 1872, and is structured in the style of medieval morality plays. In the early 1870s Morris began to experiment with printing and designing for books. The exercise was discarded when trial pages of both Love is Enough and The Earthly Paradise made it evident that Morris’s ornamentation did not sit comfortably alongside modern typefaces. Love is Enough was published without decoration in 1873.

It was always Morris’s intention to reprise his project of printing Love is Enough at the Kelmscott Press, unfortunately he passed away before he could see this take place. Morris’s executors fulfilled his wishes in printing the work two years after his death, in 1898. It was the penultimate title printed at the Kelmscott Press before it closed, the final title being A Note by William Morris on His Aims in Founding the Kelmscott Press.

This book is one of three hundred copies that were printed on paper, priced at two guineas each. The Press also issued eight copies printed on vellum that sold for ten guineas each. The book was printed using both Morris’s Troy and Chaucer typefaces and features black, red and blue ink.

The Kelmscott Press was Morris’s last creative endeavor in which he set out to revive the craft aesthetic of medieval book production in a new form, to counter the declining standards of the period’s mass production of books.

“Morris showed how a printed book might be on its own plane a work of art.” – emery walker, 1930

5:30 pm

7:30 pm

The William Morris Society

After a successful debut in 2025, we're delighted to announce the return of our exclusive Morris by Moonlight evening events! Join us after hours for a candle-lit evening at the William Morris Society Museum and experience this hidden gem by moonlight. The evening will commence with an introductory highlights talk from 6.15-6.30pm on the history of Kelmscott Read More

March 1, 2026

Join the William Morris Society this March for Morris Month. Morris Month is a month-long celebration of William and May Morris, culminating in their birthday festivities on March 24th and 25th. Alongside collaborators such as the V&A, Morris & Co., The Society of Antiquaries, The National Trust, The Ashmolean and more, every event is a chance to experience the Morris family’s creativity in new and inspiring ways.

March 9, 2026

10:00 am

4:00 pm

The William Morris Society

This workshop is now fully booked. Join stained glass artist Flora Jamieson this Spring for a hands-on workshop at The William Morris Society Museum, where participants will learn to paint their own stained glass quarry (a decorative square of glass often seen in Victorian and Arts & Crafts era stained glass windows) using traditional glass Read More

March 25, 2026

6:00 pm

8:30 pm

The William Morris Society

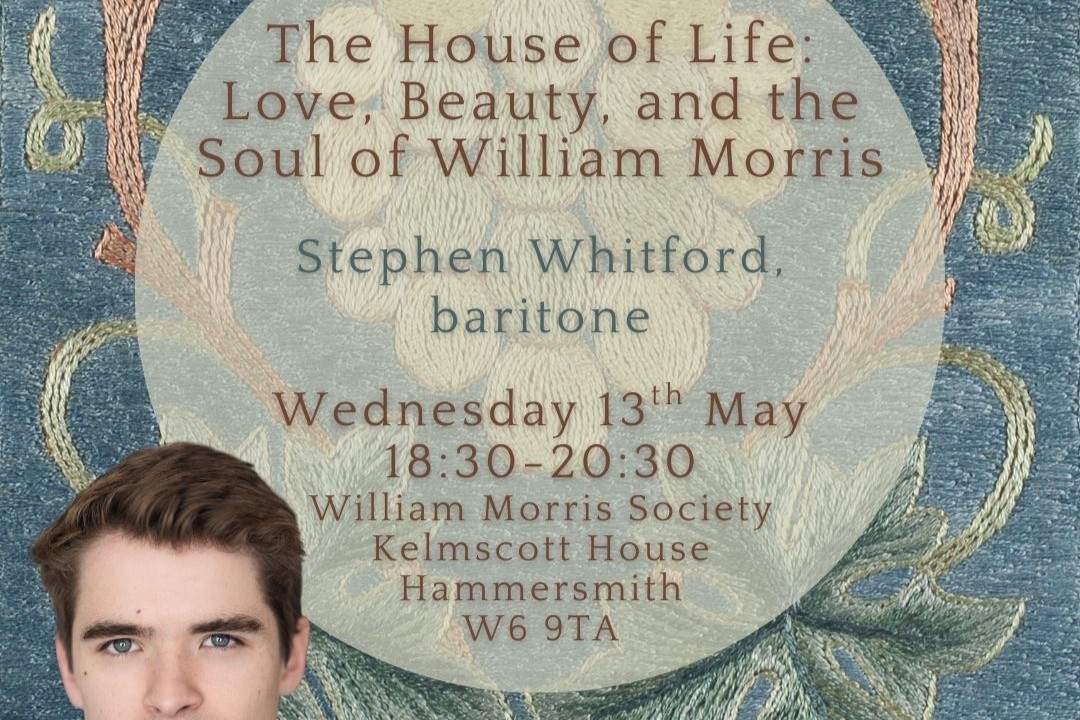

Join us in the Library for an evening of song, opera and spoken word at Kelmscott House this spring. The William Morris Society have collaborated with Opera Prelude to create the Kelmscott Series; three intimate concerts inspired by Morris’s love of beauty, nature, craftsmanship, and human connection. Blending English song, opera, and spoken word, and Read More

March 30, 2026

10:30 am

12:30 pm

The William Morris Society

Fritillary fun, bluebells, bunnies and butterflies... A workshop for children 6-12 years. Be inspired by the beautiful textiles, wallpaper and embroidery designs of William and May Morris. Come and create a basket of bluebells or a fabulous fritillary flower, and then decorate a cotton bag with your own bunnies and butterflies. Dates: Monday 30th March 10:30am-12:30pm and Read More

April 22, 2026

6:00 pm

8:30 pm

The William Morris Society

Join us in the Library for an evening of song, opera and spoken word at Kelmscott House this spring. The William Morris Society have collaborated with Opera Prelude to create the Kelmscott Series; three intimate concerts inspired by Morris’s love of beauty, nature, craftsmanship, and human connection. Blending English song, opera, and spoken word, and Read More

May 12, 2026

10:00 am

4:00 pm

26 Upper Mall, The William Morris Society, W6 9TA

This immersive one-day workshop explores the rich, tactile world of traditional block printing, drawing inspiration from the enduring designs and philosophy of William Morris. Working with Indian woodblocks, participants will discover printmaking as a slow, deliberate and deeply human craft. William Morris championed the value of the handmade over the machine, believing that beauty lay Read More

June 13, 2026

6:00 pm

8:30 pm

The William Morris Society

Join us in the Library for an evening of song, opera and spoken word at Kelmscott House this spring. The William Morris Society have collaborated with Opera Prelude to create the Kelmscott Series; three intimate concerts inspired by Morris’s love of beauty, nature, craftsmanship, and human connection. Blending English song, opera, and spoken word, and Read More

1:30 pm

4:00 pm

The William Morris Society and Emery Walker's House

This is a rare opportunity to get up close with items that are rarely on show to the public with a specialist tour of both Emery Walker’s House and the nearby William Morris Society premises. The tour will explore the Arts & Crafts textiles in both collections, including exquisite examples of May Morris’ work. The Read More